It was October 26, 1979, when my father took the call. I was sitting at the kitchen table with my on-again/off-again best friend, Teri. We were 17 years old, fresh off a Grateful Dead show the previous night, feeling pretty good about life. Something in my father’s face made me stop my conversation with Teri and stare at him. He held the phone away from his face and asked “You’re friends with Mike Miller, right?” and my heart sank because I knew that whatever the person on the other end of the phone said to my father was not good.

Mike’s car skidded on some wet leaves and he crashed into a fence. My father delivered the words softly, slowly. He stayed with the phone in his hand long after the fireman on the other end hung up. I could hear the dial tone. The only other thing I heard was the sound of my short, fierce breaths, the kind of breaths one takes before at the start of a panic attack. I didn’t look at Teri, I didn’t look at my father. I stared down at the newspaper comics I had been reading and locked eyes with Beetle Bailey.

Mike died at the hospital. He was 18 years old. He was my friend.

I’d gone to high school with Mike for a while. Senior year, he transferred from our Catholic school to a public one. We lived pretty close to each other and still met up on the weekends to smoke pot and listen to music and talk about life. We had a weird friendship — we each had our own group of friends separate from each other with no overlap, but we still made time for each other and even if it was a friendship based on getting high, there was a depth to it I didn’t share with anyone else. I adored Mike, looked up to him, even. He was popular, he was good looking, he was funny and carefree and kind. He was, for the most part, out of my league, even friendship wise. But he still chose to be friends with me, he chose to spend time with me just talking and listening when he could have been with his other friends and I treasured him for that.

I was stunned when my father told us what happened, maybe even in shock. I didn’t want to believe him, and my brain refused to accept the words he was saying. Everything slowed down. My father’s voice sounded far away. There was a heaviness in my heart I’d never experienced before and I felt like the world was suddenly drifting away from me. Mike is dead. Mike Miller is dead. Mike is dead. I kept saying the words to myself but they made no sense. Teri started crying. She wasn’t friends with Mike at all, she couldn’t have known what I was feeling and I felt weirdly resentful that she was crying when I wasn’t. But why would I cry? Mike wasn’t dead. This wasn’t real. It was a dream born of the acid we had taken at the Dead show the night before. I’d come down soon. I’d wake up. I’d call Mike.

Mike had a large family, six siblings in all. Their mother died many years before I met him, and his father did the best job he could raising all those kids. The father drove an old station wagon piled high with newspapers. The Millers lived on a corner house. And those are all the things I knew about the Millers because we never went to Mike’s house. I knew his sister, the lone girl of the siblings. I knew one of his brothers. But I knew little else about his family life. Our friendship wasn’t like that. It was something that existed on the periphery of our lives. We kept it outside everything else, outside school, outside other friends, outside our families. It existed on a plane where there was just the two of us and whether we were sitting behind 7–11 or walking the streets or hanging out in a schoolyard, there was a feel to the friendship that no one else should intrude on us. Sometimes Tommy Rollins would hang out with us. I had a crush on Tommy and I’d get annoyed when he accompanied us because my feelings toward him intruded on my connection with Mike. And I valued that connection. I needed it. It was a constant in my life and lord knows that at 17 one needs constants to keep them grounded.

I had other friends. I had a whole group of friends and we hung out and listened to music and drank terrible fruity wine while sitting under the bleachers on the football field. I enjoyed the friendships I forged with those people because making friends did not come easy to me, especially in grade school and junior high. When I got to high school and people actually wanted to be friends with me, it felt foreign. I didn’t know how to be a good friend. I didn’t know how to navigate that world. I kept most of my friends at arm’s length. But not Mike. I let Mike in. I let him into the space I had set up around me to keep others at bay. And that’s a testament to Mike’s nature, that he was able to make you feel so comfortable and safe around him you’d let down whatever guards you set up. He didn’t invade my safe space, he didn’t force his way in; it just felt natural to open up those doors and invite him in.

I spent most of November 1, 1979 in a state of shock. Teri hung around instead of going home, thinking I needed her, thinking I wanted to share this day with her. But I didn’t. I didn’t want to talk to anyone. I didn’t want to be comforted. I didn’t want to talk about it. I wanted Teri to go home but lacked the necessary words to tell her so. I went for a walk and she followed. We ended up talking a bit about it. We shared a joint and sat down on a curb and I listened to Teri talk about how this made her feel, how devastated she was, how it affected her, and all I could think was, you didn’t even know him. I was too tired, too sad to start anything with her over it. It didn’t really matter.

It was the only subject of conversation at school that week. Even though Mike had transferred, he left his mark there. People adored him. It wasn’t just me. He had still been hanging out with a lot of people from our school — the “cool” kids as it were — and there were tears and anguish and counseling. There was a moment of prayer for him during morning announcements. He was remembered by both students and staff as funny, carefree and kind. I kept quiet, kept out of the way of other people’s mourning. My friendship with Mike was outside of this realm, existed in a place where these people did not intrude. I was an outsider to them; they had no idea of the relationship Mike and I had.

My lasting memory of Mike is not a good one. We got together as usual early on a Friday evening. Tommy was there and that was ok because Tommy brought the pot, some stuff he bought from a total stranger in Alley Pond Park who told him it was “special.” Teri was there, too — it was one of the periods when I was actually speaking to her. We’d smoke and talk for a little while then we’d go our separate ways, toward our separate group of friends. I wouldn’t have any alone time with Mike that night but that was ok, because we had all the time in the world. We were 17.

There was something in the pot, I’m guessing PCP. I was not having a good experience. At one point I found myself in the middle of a four lane road, screaming that I wanted to go home, listening to cars honk at me, watching Teri and Tommy walk with their backs to me toward the 7–11 as Mike stood on the curb calling to me. Everything was happening as if in a dream and I remember not being able to tell if anything was real or not. I finally made my way across the street and I started to run toward my house, yelling things the whole time, not sure what I was yelling, just feeling like I had to yell. Within seconds Mike was there, grabbing me, forcing me to stand still, calming me down. We sat in the parking lot of the little convenience store on the corner and he talked me down from a very bad high. He stayed with me until I had myself under control and then he walked me home. Teri and Tommy were nowhere to be found. But Mike, he was there. He hung in there with me. I was embarrassed, sort of horrified at what happened.

That was the last time I saw Mike.

It’s April, 1980 and we’re getting the yearbook together. Teri is the editor, I’m on staff. I’m asked to write a little something about Mike for the in memoriam page of the yearbook. Even though he wasn’t a student there for our senior year, he was with us for the three years prior and made such an impact that he’d be included in the yearbook. So I set about writing a little essay about Mike. A eulogy. I was 17 and writing a eulogy for a friend and it just didn’t seem like a thing I should be doing. But I want to let everyone know what a good friend Mike was. I want them to know. He was my friend. He was good and kind and funny, those were things everyone knew about him. But I felt like they didn’t know the Mike I did and I want to convey that in my eulogy. So I spend a lot of time writing and thinking and rewriting.

“I’m going to write a poem instead.” This is Teri. Teri fancies herself a poet. “Instead of what,” I ask. “Instead of your thing.” My thing. My essay. My eulogy. My expression of friendship and gratitude. I was crushed. I explain to Teri about my special friendship with Mike. I tell her of my need to write this eulogy. I tell her, in no uncertain terms, that maybe someone who was actually friends with him should memorialize him.

But the yearbook goes to print with Teri’s maudlin poem in it, my eulogy just a crumpled piece of paper. When we get our yearbooks in May, I stare at that last page of it, the page with the poem, and I feel this mixture of anger and sorrow. “I’m sorry, Mike,” I whisper. “I’m sorry this is what you get.”

My friendship with Teri is over. There were other things, there were always other things, but this seals it. I go home and cry. I read the poem again and I cry. This isn’t how he should be remembered, with some bad poetry written by someone who barely knew who he was. I resent Teri for this and that resentment would stay with me most of my life.

I think of Mike around every Halloween. I think of him when the leaves scatter on the ground. I think of him during fall rains or when I pass by the old Miller house. I think about the friendship we had, that comforting camaraderie we shared, something that I’ve never been able to share with anyone else in my life. He was the brother I never had but always wanted. I think about Teri and I think about that poem and how I never let that go and thus I’ve never let Mike go. I mourn for him every year on Halloween. I mourn for all the conversations we never got to have.

I sit here now, 41 years after Mike died, 41 years after sitting at my kitchen table numbed by the words my father spoke to me. I sit here and I write about a friend I had three decades ago, a friend like no other. I sit here and write what amounts to a eulogy for him, so many years later. Because I want you to know what I wanted all his peers to know, what I wanted the world to know back then.

Mike was good and kind and funny. Mike was my friend, my confidant, my platonic soulmate. I learned a lot from him in life, and I learned so much from him about death.

Be careful driving on wet leaves. And don’t buy pot from strangers.

This is my 41 year old eulogy.

Rest in peace, Mike.

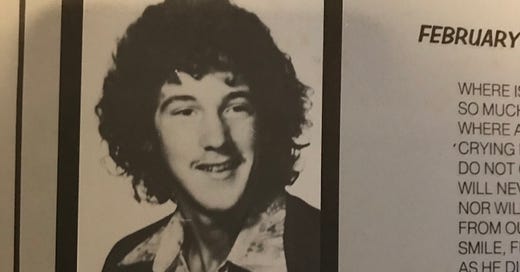

[picture is from my yearbook. i cut off teri’s poem on purpose]

Far too few Mike’s, far too many Teri’s. RIP.